Research - Atmospheric Boundary Layer Turbulence

Atmospheric Boundary Layer Turbulence

Turbulence is a chaotic and powerful phenomenon in fluid dynamics, influencing everything from weather patterns to air quality. It’s what creates the swirling motion in clouds, drives ocean currents, and plays a key role in climate and pollution movement. My research focuses on a particular kind of turbulence called stably stratified turbulence, which occurs in layered environments like the atmosphere and oceans, affecting both natural processes and human activities.

What is Stably Stratified Turbulence?

Stably stratified turbulence happens when there’s a stable layering in fluids, like warm air sitting on top of cooler air. This stable layering, often due to temperature differences, prevents vertical mixing and keeps the air or water layers mostly separate. A key factor controlling this is the Richardson number (Ri), which is used to predict when turbulence will weaken or stop. When Ri is high (above a certain threshold), turbulence decreases, and the fluid layers remain intact.

In most types of turbulence, energy moves from large swirls down to smaller ones until it fades. But in stably stratified turbulence, this downward “cascade” is interrupted. Instead, energy often flows horizontally, forming layered, wave-like structures. My research examines how these layers generate internal gravity waves—oscillating motions that play a major role in energy transfer across these stable layers.

The Role of the Atmospheric Boundary Layer (ABL)

The atmospheric boundary layer (ABL) is the lowest part of the atmosphere, where the Earth’s surface directly influences the air above. It can stretch from a few hundred meters to a couple of kilometers, depending on the terrain, weather, and time of day. The ABL is critical for weather and climate because it’s where air masses mix, affecting everything from daily weather to long-term climate patterns. In stably stratified conditions—often occurring at night or under high-pressure systems—turbulence is much weaker, which changes how air mixes.

A key area of my research is the nocturnal boundary layer (NBL). After sunset, the ground cools, creating a temperature “inversion” where the air above is warmer than near the ground. This setup reduces mixing and traps pollutants close to the surface. In the NBL, turbulence tends to be intermittent, and the lack of vertical mixing sometimes leads to a low-level jet, a narrow band of fast-moving air that moves pollutants and heat horizontally.

Studying Stably Stratified Turbulence

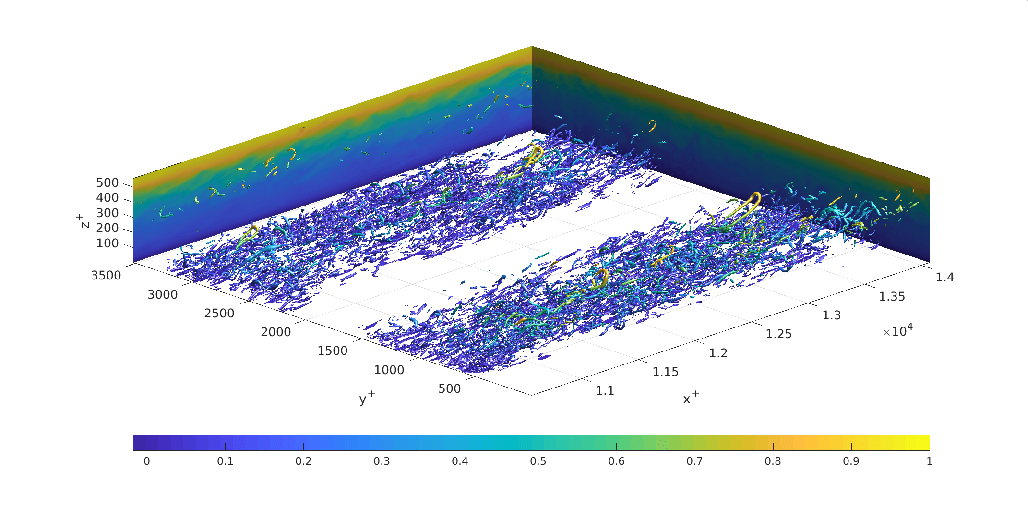

To understand these processes, I use numerical models such as large-eddy simulations (LES) and direct numerical simulations (DNS). These models replicate buoyancy effects and layering dynamics, though resolving the fine details of wave-turbulence interactions remains computationally challenging.

Why This Research Matters

My research on stably stratified turbulence in the ABL is essential for several reasons:

-

Weather Forecasting: Accurately representing stable layers improves predictions for nighttime weather and stable high-pressure conditions.

-

Climate Modeling: Long-term climate models rely on a precise understanding of how stable stratification affects heat and moisture movement in the ABL.

-

Air Quality: During stable conditions, pollutants are often trapped near the surface, reducing air quality. Insights from my research help in predicting pollution behavior and improving mitigation strategies.

-

Aviation Safety: Internal gravity waves and turbulence in these stable layers can impact aviation. Enhanced models and forecasts improve flight safety under these conditions.